Fact: Jerry Uelsmann and Maggie Taylor are (or were in his case) photography world royalty. The work of these widely collected image-makers hangs in major museums around the globe, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art; Museum of Modern Art, New York; The National Gallery of Art,Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles County Museum; and the Royal Photographic Society and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

In memory of Jerry Uelsmann (June 11,1934 – April 4, 2022), Slate Gray South presents “Doorways of Ominous Portent,” featuring the work of the former husband and wife team married for 25 years (until 2016).

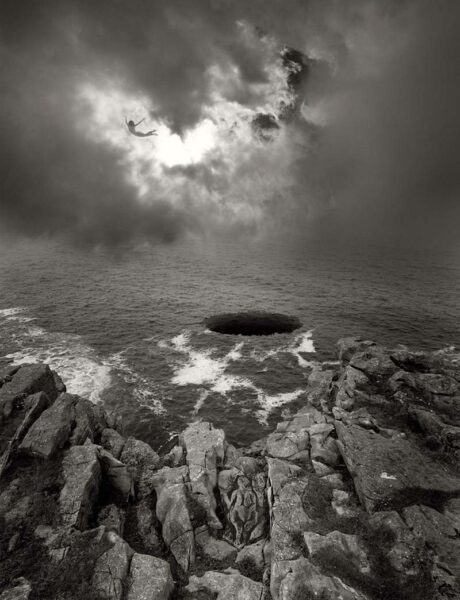

“I have gradually confused photography with life and as a result of this I believe I am able to work out of myself at an almost precognitive level,” Jerry Uelsmann once told Telluride Inside.. and Out.

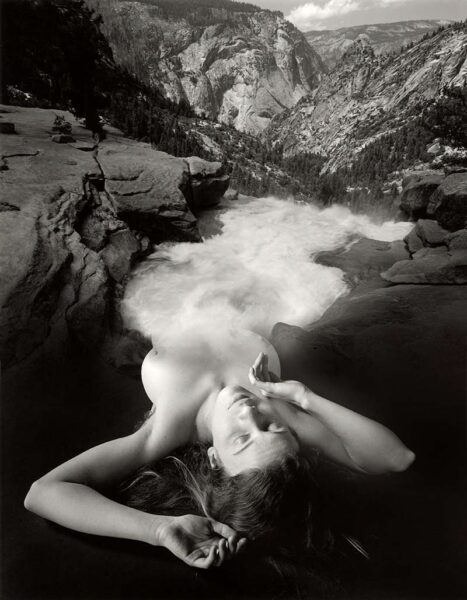

Uelsmann, Waterfall Figure Yosemite, 1987.

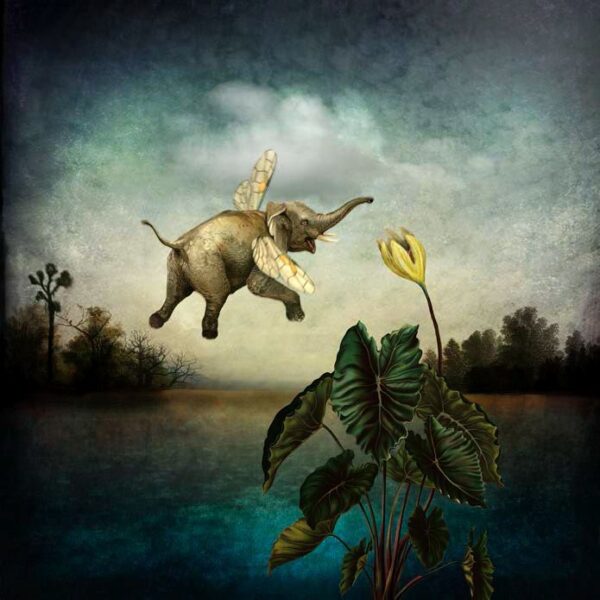

Taylor, The Weight of the World.

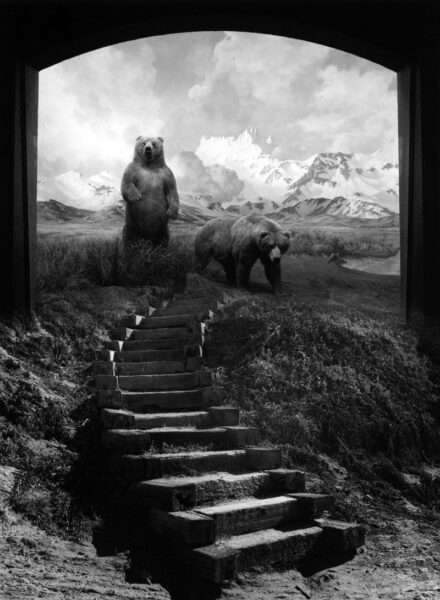

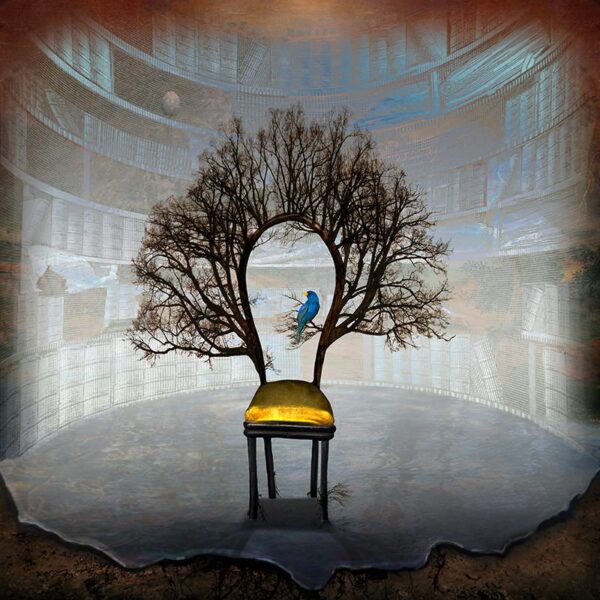

Heirs to the Surrealist tradition the 1920s and 1930s, Uelmann’s black-and-white composites and Taylor’s computer-generated color montages sport improbable juxtapositions that reveal subconscious impulses, the world of dreams, mysticism, and Jungian archetypes from the collective unconscious.

A natural response to images from the shadow world is to try to find the artists’ hidden meaning, then wax poetic on the symbolism. Try not to go there. Both artist have insisted there is no one right interpretation. There is only your interpretation.

In an interview back in 2003, Uelsmann explained:

“Maggie and I are both sympathetic to the notion that we invent realities or super realities, that are personally more meaningful to each of us than what is outside our windows. These super realities are based on the wonderful and interesting stuff we have enshrined in our minds or stuff that was already there that definitely reflects our psyches. Confronted with our images, viewers are forced into a sort of internal dialogue between what they know intellectually about photography and what they are being shown. The inventive consciousness of our viewers becomes another part of the picture. You don’t necessarily see what I see and that’s just fine. Absent straightforward subject matter, you have to rely solely on your personal responses. Since our work falls into the narrative tradition, it appeals to the mind as well as the eye. Scholars have drawn analogies to lyrical poetry.”

Uelsmann, Bears and Stairs, 1996.

Taylor, Is This a Chair?

In the early 1950s, Uelsmann attended the Rochester Institute of Technology where he studied with photography legend Minor White. For White the goal of a serious photographer was to get from the tangible to the intangible to create visual metaphors:

“One should photograph things not only for what they are, but also for what else they are,” White once said.

One of White’s assignments back then was a project he titled “Doorways of Ominous Portent.” To Uelsmann, the phrase gave insight into how photographs could function the way White explained, metaphorically or beyond what is revealed in the image.

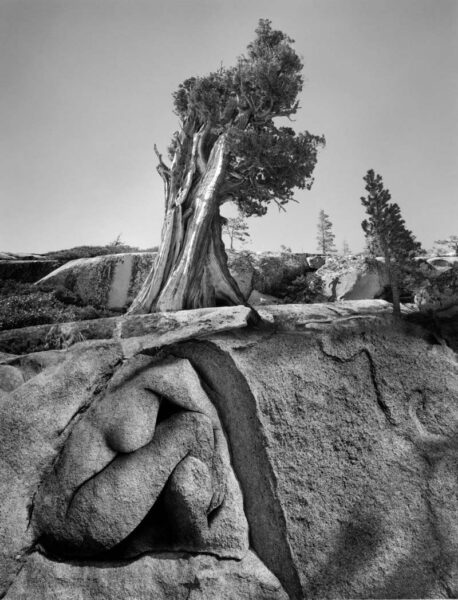

Uelsmann, The Alpha Tree.

By the 1960s, Uelsmann was creating his dramatic photomontages, considered unsettling alternatives to the prevailing naturalism of the time.

A virtuoso in the darkroom, Uelsmann pioneered and perfected new developing techniques. On three or more of the eight enlargers in his Florida darkroom, he combined parts of all of two or more negatives, which he burned and dodged (exposed sections to more or less light) to make his final, seamless black-and-white, now legendary prints.

Uelsmann used to describe his unique way of working as “in- process” discovery or “post-visualization” in contrast to Ansel Adams’ “pre-visualization.”Adams taught photographers to see in their minds what they wanted to create at the moment of exposure. Uelsmann encouraged his colleagues to re-visualize an image at any point in the photographic process. Drawing an analogy to creative writing, Uelsmann once told us:

“Sometimes an idea which seems trite becomes your content. You don’t know until you start writing. I allow myself to wonder constantly what would happen if….”

Uelsmann, Figure in Rock, 1997.

Over the years Uelsmann continued to explore and improve upon his bravura darkroom techniques, yet his symbolic vocabulary remained surprising consistent: nature and culture cross boundaries when interiors meld with exterior landscapes. Figures levitate or fly. Monumental hands, a classical element in Surrealist photography, appear everywhere.

Bizarre, even grotesque, surrealist themes prevail: disembodied human parts; humans merging with trees, rocks and water; animals, vegetables and minerals blending and intertwining.

Fast-forward to 1995, when the creative director of Adobe tried to entice Uelsmann into making his images using an upgraded computer loaded with Photoshop.

But Uerlsmann refused to bite, preferring his aforementioned, painstaking, darkroom dance. However his wife, Maggie Taylor, became intrigued with the many and varied possibilities the software app offered and started experimenting.

Uelsmann, Magritte’s Touchstone.

Taylor grew up in the 1960s/1970s, when social commentary was the name of game in the work of Pop artists such as Andy Warhol. Taylor’s images, however, are less social commentary and more personal statements, often, though not always, with a feminist cast.

Taylor, The Philosopher’s Study.

In her studio, Taylor has drawers and shelves filled with all kinds of objects and pieces of text. She also collects and “recycles” Daguerreotype or Tin Type portraits of unknown subjects from the 19th-century. The artist choreographs this detritus of her life indoors before taking the items outside into her yard to photograph them with an old view camera in natural light. An avid gardener, Taylor also finds inspiration, as well as actual material to scan, when outside. She builds stories around her subjects by combining her own photographs with scanned objects to create digital collages in Photoshop, using as many as – wait for it – 200 layers!

Taylor, What Remains?

Like most artists who make emotionally impactful work, Taylor creates from “personal experience, from my own memories and dreams – from my psyche.” The resulting images are humorous, whimsical and reminiscent (with a wink) of the work of Magritte and Dali. Her work explores deeper archetypes too, perhaps a tip of the hat to her philosophy degree from Yale. (Taylor also holds an MFA in photography from the University of Florida.)

“Often when people think about using the computer to make art, they mistakenly think that it is an easy solution or a very quick process. In my experience, using the computer is slower than working with a camera and film. I go back again and again to the images and refine and improve them. I only make about 10 to 15 images a year and I can be working on one image for a few weeks or even a month. That said, for me, both computer and camera are great ways to document, as well as transform reality,” explained the artist.

Taylor, Anything But a Regular Bee.

Taylor’s goal?

“I want my viewers to experience a convergence of factual memory and fictional day dreams, which is similar to my own internal dialogue in creating the work.”

Bottom line: Taylor’s technically brilliant, unapologetically enigmatic digital photographs throw the viewer slightly off balance, like the work of her former husband, which tends to conjure Jungian archetypes.

“The dreamlike world of narrative photomontages – Alchemist. Weaver of narrative collages. Image magician. Maggie Taylor and her work defy traditional labels..,” explained on The Photoshop website.

“(I am) interested in creating a cohesive, visual, believable space the viewer can visually enter… “Ideally, I want the images to invite the viewer to engage and recollect, almost like entering a stage set or a scene from a dream,” explained Taylor on the same site.

Uelsmann, Place of Several Mysteries.

Taylor, Happily Ever After.

“Jerry Uelsmann’s work transcends surface reality through photo manipulation in the darkroom; Maggie Taylor gives vintage and unusual items new life through modern technology. Both artists create ‘Doorways of Ominous Portent,'” said the show’s curator, Slate Gray gallery director Krissy Kula.

Written By