“We must not limit ourselves to looking at nature from the outside, but we must live it from the inside,” philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Joseph Toney in a nutshell.

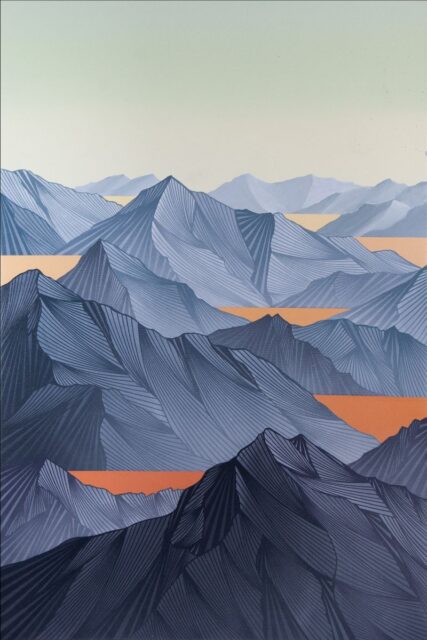

The artist lives in and loves the vastness of the American West, a passion his abstracted memory-scapes reimagine in Toney’s signature minimal, abstract, and illustrative painting style.

“In my work I want to create a sense of liveliness and energy that reflects how I feel when spending time in these places. Along with this, I utilize processes and materials that reflect on our changing environment,” Toney once said.

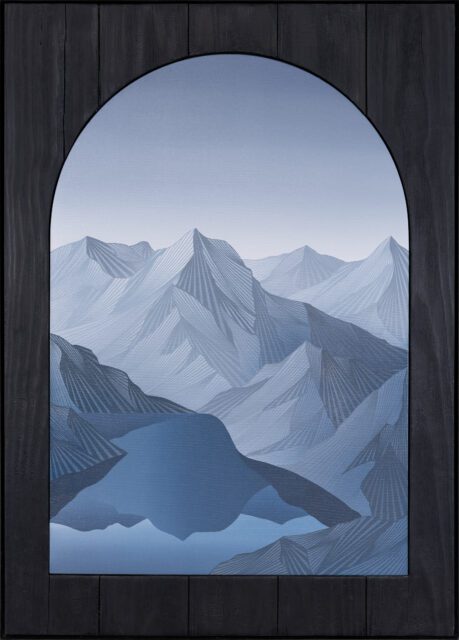

Toney’s upcoming show at Telluride’s Slate Gray Gallery, titled “Points Unknown,” pays tribute to the Telluride region’s San Juan Mountains. The show will also include a mural Toney plans to paint on site.

“My new work marks a significant departure from previous exhibitions at Slate Gray. While the underlying themes remain similar, this is the first series of mountain paintings I’ve created in full color. Drawing on years of experience using color as a designer and in my large murals, I have incorporated that knowledge into my studio practice. The shift has opened new doors on how I approach composition and structure these ‘new landscapes.’ Previously, I would often focus on depicting single mountain peaks, but this recent work captures the land on a larger scale, combining multiple locations across the San Juan Range into a single composition. My work has also become more abstract, while still offering familiar vantages.”

When fire rages through dry underbrush, it clears thick growth so sunlight can reach the forest floor and encourage the growth of native species. Fire frees these plants from the competition delivered by invasive weeds and eliminates diseases or droves of insects that may have been causing damage to old growth. Wildflowers begin to bloom abundantly.

And, in the rare case of artist Joseph Toney, the aftermath of major conflagrations yielded a new technique, which enhances his simply elegant images, the artist’s marks serving as metaphors for humankind’s marks on the pristine wilderness environments he celebrates:

“I often strive to create an environmental connection in my work. Our world is constantly evolving, and our changing climate has inspired me to create pieces that reflect this. For example, while camping in the High Uintas, I stumbled upon a forest burn and collected charred remains from ponderosa pine and aspen to use later in the studio. The medium is challenging to work with because it is not as consistent as store-bought charcoal. I have used it as a pigment to sketch compositions on canvas and to do some initial shading. Then, I apply acrylic washes and opaque paint to finish the painting. By incorporating materials harvested from the physical location that inspires the work, I aim to initiate conversations about our changing environment, land conservation, and what we can do to protect what we love.”

To learn more check out TIO’s interview with Toney.

Jospeh Toney in his studio. Credit, the artist.

TIO: Do you come from a family of artists or are you a genetic anomaly? In other words, what triggered Young Joseph’s interest in fine art?

JT: I do not come from a family of artists. There are more engineers and landscape architects in my family lineage than anything else. My dad has been a lifelong musician, but his career led him into tech and later into teaching as a college professor.

TIO: You started making art in high school. What got you going?

JT: At the time one of my elective courses was architectural design. However, that discipline felt a little too rigid for my liking, so I switched all of my electives to art courses instead.

TIO: You spent your sophomore of college in Austria and Germany studying design in Dornbirm. Who pointed you in that direction and how did your studies in that toy town impact your future as a professional artist?

JT: My father taught an entrepreneurship course at the same university in Austria. They eventually set up a study abroad design course in English and I was the first student from my American school to head over for that program. It was eye opening to see how design was being taught in Europe versus in my small, rural, North Carolina hometown. I had a few opportunities locally then to create board graphics for an Austrian Skateboard brand which helped me to start building a more professional portfolio.

TIO: You worked for Teton Gravity Research and Armada Skis. How did your commercial work feed into your fine art. Or did it?

JT: I spent the better part of a decade working as a commercial graphic designer in the outdoor industry. At the time I worked for numerous other brands along with the ones mentioned above. As a commercial designer it is helpful to have the knack to work in multiple design styles and aesthetics. When fitting, I’d sneak my own art practice into what I was designing. That time period was formative for me because I was experimenting with a lot of different art practices to create top sheet graphics for Armada Skis and Jones Snowboards.

Sometimes those would be executed as watercolors, mono-prints, collages, illustrations, paintings, and photographs.

TIO: Two of your major influences are Chinese scroll art and Cubism. Please describe how East meets West in your art.

JT: Those have certainly been sources of inspiration. I was also often drawn to the limited palette and mediums found in traditional Japanese landscapes. That influence may have shown through more in my earlier work than it does now.

However, the Cubist’s approach to show the same thing from multiple perspectives remains a technique I employ in this new body of work. Instead of choosing to represent a subject from one singular point of view, like a snapshot in time, I am creating works that combine hours, sometimes days of impressions, into singular compositions. The new work may offer familiar vantage points to the residents of the San Juans while, at the same time, the images share a new and distinctive perspective. A perspective that could have only been seen and visually combined if you were following along with me on a physical journey through the land seeing, for example, the same landscape at different times of day and from different points of view.

TIO: Please describe your creative process which I believe begins with a photograph.

JT: When gathering inspiration for a painting I try to spend as much time as possible on location. I think I logged close to two months camping last year. On those trips I am outside recreating with a camera in tow, or sometimes just using an iPhone. Regardless, I take countless reference photos along the way which I later use to sketch out a new composition.

TIO: You have painted a number of major murals, including in Colorado, New York and Utah, I believe based at least in part on the role humans have played in the landscape and using what you have described as “found carbon.” Please talk about those projects and the mural you have planned for the Slate Gray Gallery.

JT: Painting murals has been a significant part of my professional practice. I have had the privilege of painting across the nation, with a primary focus on the Mountain West.

For non-commercial projects, I aim to create works that raise awareness for the environmental issues I care about. One such piece is in Midvale, UT, designed to draw attention to the Great Salt Lake. During years of low water levels, an island that had once been a major rookery site for pelicans completely disappeared, threatening their habitat. The mural depicts a large pelican and clouds bringing new water to the region. It was painted just before two major snow years that helped refill the lake. However, much work remains to ensure the lake has enough water for future generations.

The mural I will be creating at Slate Gray will directly connect with one key painting in the show and may also complement another piece. The mural should then augment the impact of the paintings, inviting viewers to gaze up at mountains within the gallery, much like a hiker looks up towards the summit of a peak.

Written By