28 Aug Slate Gray Sept: “Holy Land U.S. A.,” Cinematic Photography by Lisa Barlow, 8/29-9/10!

Slate Gray Gallery enters the fall season with a series of shows at the venue.

First up August 29 – September 10: “Holy Land U.S.A.” The show features the cinematic photography of Lisa Barlow. On Thursday, August 29, 4:30 p.m., author Phillip Lopate will share his thoughts about the economic, yet intrinsically moving images.

Note: “Holy Land U.S.A.” is also the title of Lisa’s new book, which includes all the images at Slate Gray and then some. The book is slated to come out in October, but copies will be available at Slate Gray and Between the Covers Bookstore. “Holy Land U.S. A.” can also be pre-ordered through the Stanley Barker website.

Next up: “Panoramas,” which features the work of local Brett Schreckengost, September 5 – September 29.

September at Slate Gray also showcases the work of two fine art jewelers, Tana Acton, September 13 – September 15 and Nanci Modica, September 26 – September 30.

Go here for more about Slate Gray.

Fine art photographer Lisa Barlow.

Lisa Barlow’s “Holy Land U.S.A.” is on display at Telluride’s Slate Gray Gallery in the run-up to the Telluride Film Festival. The show reveals a fine art photographer who is completely comfortable in her own skin – and when focusing her lens on whatever, well, clicks. She summed up that fact of her artistic life with a simple statement about the locals of Waterbury, Connecticut, the “set” of Holy Land.

“I spent so much time with these people they began to feel like family.”

The images in the show are open, honest, empathetic, direct, and spiced with a dry sense of humor, underlining an old trope: any good artist shows what he or she is through their work. Lisa clearly has the talent, the eye, the nimbleness and the wit to speak in many voices at once. Her photographs are not about impressing; they are about making her viewers feel, making us all live those particular moments in time.

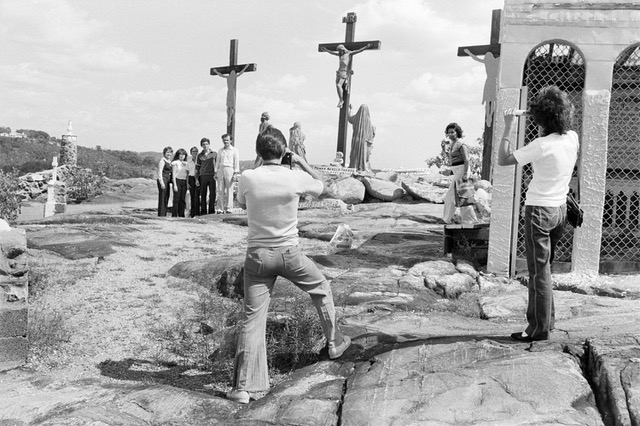

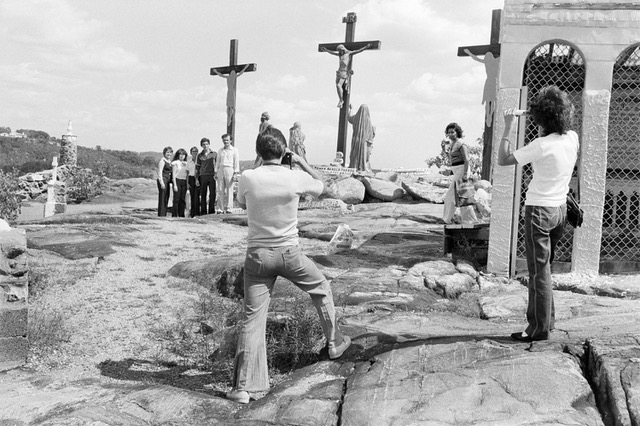

Lisa Barlow © Holy Land USA.

Lisa Barlow (C) Holy Land USA.

Lisa Barlow (C) Holy Land USA.

Lisa Barlow (C) Holy Land USA.

Lisa Barlow © Holy Land USA.

“Holy Land U.S.A.” unrolls into a horizontal and raw visual narrative that feels cinematic – no big surprise given that one of Lisa’s muses was (and remains) Ken Burns, a world-famous documentary filmmaker and titan of truth-telling:

“When telling a story about a real place, it is okay to be influenced by fiction, but Ken is the master of staying true to the facts,” explains Lisa. “He takes what we think we know and amplifies that. With every story Ken tells, we know more and feel more with his telling. And we always end up knowing more about ourselves.”

Lisa took the photographs for “Holy Land U.S.A.” in 1980 and 1981 when she was an American Studies major at Yale.

“Waterbury, as you might remember from Ken Burns’s WWII documentary, was once the ‘Brass Capital of the World,’ famous for the bullets and buttons it produced. But, by the time I discovered it, the city had fallen on harder times. Factories were empty and houses tattered, yet the poise of the city remained in its gracious layout, the august trees lining its streets, and the monumental brick buildings that abutted the river running through town.

“First fascinated by the huge cross looming over the city and the little diorama of Jerusalem and stories from the bible beneath it, I grew to understand that the people I began to meet in the town had the more interesting stories to tell.”

Part of Lisa’s own story has to do with the relationship between still photography and moving pictures two disparate, yet very connected siblings and inventions.

How so?

At its core, cinema, with its close-ups and freeze frames, is basically an animated form of still photography. That reality, now almost too obvious to state out loud, was made real around 1895 when the Lumiere Brothers screened their first film. Since then, intrepid innovators like Robert Frank and Helen Levitt have felt comfortable going back and forth between photography and film. And both also happen to be major influences on Lisa Barlow’s simply elegant work.

Like all of us cinephiles, Lisa is a voyeur, but one who turns that pastime into an art form. In “Holy Land U.S.A,” her photo-stories suggest the harsh reality of geographic, economic, racial, and religious diversity in the US. But with a warmth that forces a smile. There is something metaphysical in Lisa’s ability to render ordinary people in ordinary moments iconic through the multiple “frames” of this haunting show.

For more, check out TIO’s interview with Lisa Barlow.

TIO: Who or what were your earliest influences as a photographer?

Lisa: My earliest influences as a photographer came from the work I got to know in high school. Henri Cartier-Bresson helped me see how to organize the world within a frame. Robert Frank and Diane Arbus awakened me to the idea that one can convey powerful, outside-the-envelope ideas through images. But it was other mediums that helped me understand the mechanisms of story-telling. I loved the way short stories, novels, plays and films created whole worlds to inhabit.

TIO: American author and journalist Brad Zellar saw your Holy Land images a few years ago and wrote an essay about this body of your work, reinforcing the collection’s ties to film. Please drill down to the heart of what Zellar had to say.

Lisa: Brad Zellar seems to have tapped into my love of film and theater when he wrote: “These images work on me in a way that photographs rarely do, in that they really seem to move, to speak, to breathe; there’s music in them, songs and stories that rise from them unbidden. When I first began to look seriously at ‘Holy Land U.S.A.,’ so many of these photographs felt like film stills from some vaguely familiar movie, but after a couple weeks of staring into them and following them from page to page, time and again I turned away with the vivid sense that I had actually seen a movie. And, over time, they really have become a world to me, and I’m just sharp enough to recognize that as a gift.”

TIO: Synchonicity or serendipity at play: your show at Slate Gray aligns with the Telluride Film Festival (TFF), an event which includes a few of your major influences.

Lisa: In high school, opera, film, theater, festival director and resident curator of the TFF, Peter Sellars, was one year ahead of me at Andover. An inimitable genius even then, the “Peter Sellars’s Extravaganzas” were a series of one-act plays he produced in our campus black box. I was lucky enough to act in at least one of them, forever transformed by Peter’s brilliance.

The situations on stage might have been outwardly preposterous, but they were always true, always a vessel for larger ideas.

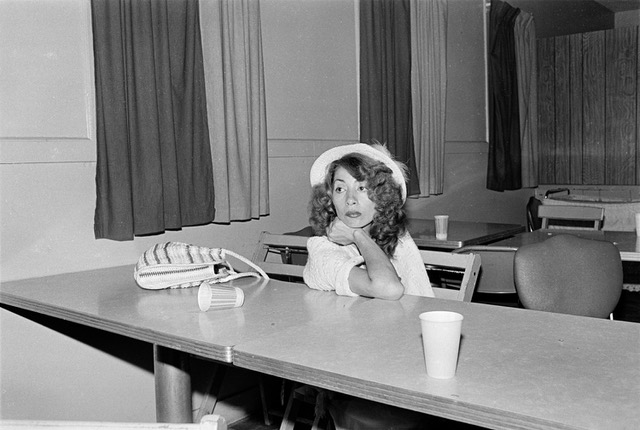

Peter Sellars, courtesy Lisa Barlow.

Annettte Insdorf served as Columbia University’s Director of Undergraduate Film Studies for 27 years. She is also one of TFF’s regular speakers. In college, I found myself a sophomore in one of Annette’s film classes on Francois Truffaut and Alfred Hitchcock. As in literature classes, Annette had us break down the manner in which a story is created. How, using whatever techniques, are we carried along to a new and deeper understanding of the subject at hand.

Annette Insdorf, leading a panel at the Telluride Film Fest, courtesy Lisa Barlow.

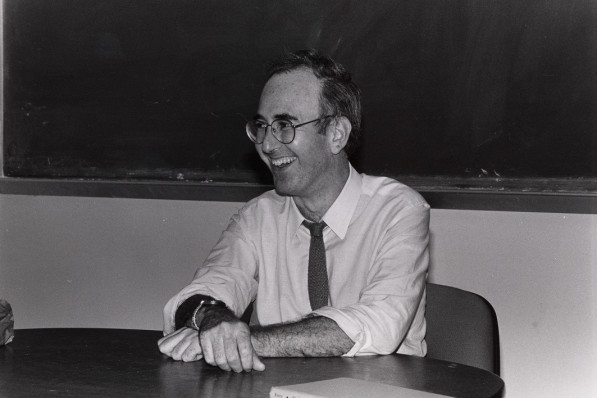

Later, it was Phillip Lopate, whose essays I enjoyed as a reader. He helped advance my understanding about the myriad ways artists, especially film-makers, can link ideas that can shape our experiences.

Phillip Lopate, courtesy Lisa Barlow.

And then there was the aforementioned Ken Burns.

Ken Burns, Steve Holmes Photography.

That all four of these artists are such passionate TFF supporters and attendees allows me the chance to publicly thank them for helping to shape me as an artist.

TIO: Anything else to add?

Lisa: I’m tremendously grateful to Beth McLaughlin and Allison Cannella at Slate Gray for the chance to share this chapter of my work.

Written By